Curious Questions

One main thread of my novel, The EarthStar Solution, follows Kaye, the daughter of a hedge fund manager, as she tries to challenge her father’s climate denial. She starts out ambivalent about the issue herself, based on his assertions over the years, until circumstances convince Kaye he may have been lying to her. In writing the story, I wanted the discussions that Kaye has with her father to be difficult because we all know how emotional it can be talking with each other in this current polarized climate, and I wasn’t sure she should even be successful in turning him around. Can you ever change someone else’s mind?

It might be easier than we believe to make a dent in the stubborn political divide that we face. I stumbled onto an article in Scientific American from 2018 about how our political opinions are more flexible than we think. Called “How Political Opinions Change,” the article explained that people are highly defensive of their opinions that align with their social group. Therefore, the authors, Philip Pärnamets and Jay Van Bavel, claim through their research, in order to open people’s minds:

the trick, as strange as it may sound, is to make people believe the opposite opinion was their own to begin with.

In their experiment, they gave false-feedback about participants’ original choices concerning actual political questions before asking them to restate their views at a later time. The false-feedback worked, showing people shifting their stances to align more with the false feedback, revealing that their initial opinion was more flexible than they might have imagined.

When I read this, I was a bit repulsed. This was hardly a solution to the denial of climate change that is hampering efforts to repair our climate. It seemed on par with propaganda and brainwashing as something to avoid, but Pärnamets and Van Bavel were not advocating it as a solution at all. They instead hoped that this research could show us how the polarization that grips the country is not as intractable as it seems. Opinions can change if we understand that the basis for them may have more to do with the social/political groups we associate with than we realize.

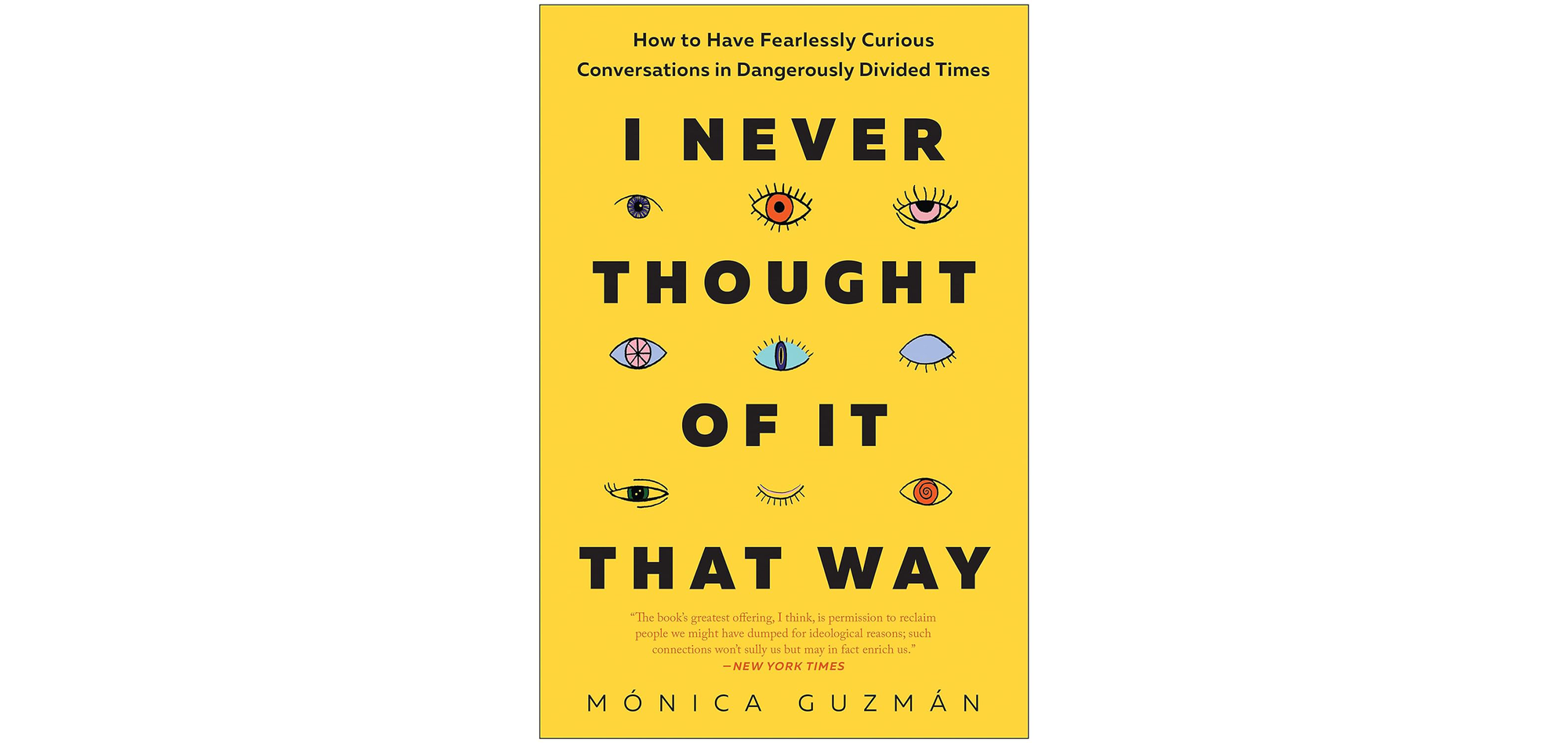

But I wasn’t going to base Kaye’s discussion with her father on trying to trick him into a new opinion. I needed a better way for her to dialogue with him. One of the resources I read is a great book about how to have discussions with those you disagree with. I Never Thought of It That Way by Mónica Guzmán is a how-to about having “fearlessly curious conversations in dangerously divided times.” It’s not really about changing someone’s mind. Instead, it is about crafting a conversation with someone to understand their point of view and to share your own.

Guzmán calls these discussions bridging conversations and the book is filled with suggestions on how to keep talking so you don’t storm out of the building totally frustrated. I think it is an important book, but also a challenging book to actually apply in real life. How do you stop yourself from blowing up at someone who believes climate change is a hoax? How do you stay curious about them without accusing them of putting your grandchildren at risk or causing the collapse of whole ecosystems?

Part of the answer, according to Guzmán is questions. Her book is full of questions you can use to pull information out of someone and make it a genuine sharing opportunity. Instead of gotcha questions, trying to win an argument, these questions get triggered by a deep curiosity to understand the other persons life experience and how they came to their conclusions.

I can’t list all the questions sprinkled throughout the book, but here is a sampling:

1. How to switch from trying to win to trying to learn? Ask “What makes each perspective understandable?”

2. How to keep curious in the conversation? Ask yourself, “What am I missing?” or “Can I believe it?” or “Where are you coming from?” to fill gaps in your knowledge about what the other person is saying.

3. To probe their experiences that helped shape their opinion, ask “How did you come to believe X?” and try to elicit the stories from their lives to answer this question by asking when or where those ideas came to them.

4. To find out about their values that underlie their beliefs, ask about their concerns that flow from the issue or their hopes about the issue: “What concerns you about X?” or “What do you hope can happen with X?” or “Why isn’t that a concern (or hope) for you?” and even, “What do you care about more?”

5. Get hypothetical. Ask a what if question: What if X… How would that change our view of this?”

6. Clarify: Ask “Can I repeat that back to you just so I know I’ve got it?”

And it’s not only about the questions. There is much more in the book about how to tackle the assumptions we make concerning the other side, as well as how to listen well to their answers, but most importantly, how to share our side of the issue as well.

I can’t say that I used all Guzmán’s wisdom in my story, but it certainly came into play at points of the plot. I also can’t say that I’m now a wise bridging conversation builder, mostly because I don’t have many opposing personalities in my circle. It was a good read, however, which is why I am recommending it to anyone on either side of the aisle. It would be nice for all of us to attempt having these difficult conversations in our divided world, and we just might find better ways to address the looming crisis of climate change together in ways we didn’t expect.

Member discussion